Nanchang Uprising (Information)

Release time:

2018-02-25

Lin Pi Bian

After the Wuhan Nationalist Party led by Wang Jingwei publicly turned counter-revolutionary on July 15, 1927, the military and political situation in the provinces under the rule of the Wuhan government became extremely perilous. Militarily, the Fourth Army, Eleventh Army, and Twentieth Army of the Second Front Army of the National Revolutionary Army, influenced by the Chinese Communist Party, had been transferred to the areas around Jiujiang and Nanchang; the reactionary forces of the Nationalist Party, led by Zhu Peide, stationed the Third Army and Ninth Army in Zhangshu and Linchuan, while Cheng Qian's Sixth Army concentrated towards Nanchang, creating a situation of encirclement against the Fourth Army, Eleventh Army, and Twentieth Army. Politically, the Wuhan government had completely turned reactionary, with Wang Jingwei, Tang Shengzhi, and others crazily slaughtering our party and suppressing the workers' and peasants' movements; although the commander of the Second Front Army, Zhang Fakui, still expressed opposition to Tang, he had already been deeply influenced by Wang and expressed dissatisfaction with us, wanting to 'have CP members among the senior officers of the Second Front Army, such as Ye Ting, withdraw from the army or leave the CP.' However, all these evil actions of the counter-revolutionaries did not suppress the revolution. The peasants and workers in provinces like Hunan and Hubei continued to fight under the brutal white terror, even launching armed struggles in some areas. Based on the situation at the time, the Central Committee decided to hold the Nanchang Uprising. Comrades such as Zhou Enlai, Yun Daiying, Peng Pai, Wu Yuzhang, Lin Boqu, Liu Bocheng, Nie Rongzhen, and Li Lisan successively went to Jiujiang and Nanchang to prepare for the uprising. Some units of the Fourth Army and Eleventh Army, influenced by Ye Ting, and the Twentieth Army led by He Long also concentrated towards Nanchang, preparing to disarm the Third, Sixth, and Ninth Armies stationed in Nanchang. On July 27, according to the Central Committee's order, the front committee, with Zhou Enlai as the secretary, was officially formed in Nanchang and was scheduled to launch the uprising on the evening of the 30th. However, on the morning and noon of the 29th, Zhang Teli (later known as the traitor Zhang Guotao) suddenly sent two secret telegrams from Jiujiang to the front committee, stating that the uprising should be cautious and must wait for him to arrive before making a decision. At that time, the front committee believed that the uprising could not be stopped and continued all preparations. On the morning of the 30th, Zhang Teli arrived in Nanchang and held a front committee meeting. Zhang Teli said: If there is a good chance of success for the uprising, it can be held; otherwise, it should not be initiated, and comrades in the army can withdraw to work among the peasants. Zhang also said that given the current situation, efforts should be made to win over Zhang Fakui, and the uprising must have Zhang Fakui's consent; otherwise, it should not be initiated. At that time, Zhou Enlai, Yun Daiying, Peng Pai, Li Lisan, and other comrades unanimously opposed this opinion, stating that the uprising must not be delayed or stopped; Zhang Fakui, influenced by Wang Jingwei, would never agree to our party's plan; our party should stand in a leading position and could no longer rely on Zhang. After hours of debate, no conclusion was reached. On the morning of the 31st, another front committee meeting was held, and after several hours of debate, Zhang Teli had no choice but to finally express his compliance with the majority. Thus, the front committee decided to launch the uprising at 4 a.m. on August 1. The uprising order was drafted by Comrade Ye Ting and issued in the name of Comrade He Long (acting commander of the Second Front Army). Unexpectedly, an officer surnamed Zhao from the First Regiment of the Twentieth Army leaked the secret and informed Zhu Peide's subordinates about the uprising plan. Zhu Peide immediately prepared to resist. In this situation, the front committee decided to advance the uprising by two hours, but ultimately, due to the enemy's preparations, the uprising army faced many difficulties, and by 6 a.m., the Third, Sixth, and Ninth Armies in Nanchang had completely surrendered.

After the victory of the uprising, the Central Revolutionary Committee (referred to as the Revolutionary Committee) was established. Under the Revolutionary Committee, there were separate party affairs committees, advisory groups, peasant and worker committees, propaganda committees, financial committees, secretariats, general political departments, political security offices, and other agencies. The army continued to use the designation of 'National Revolutionary Army.' Comrade He Long served as the commander of the Twentieth Army, overseeing the First, Second, and Third Divisions; Comrade Ye Ting served as the commander of the Eleventh Army, overseeing the Tenth, Twenty-fourth, and Twenty-fifth Divisions, but the Twenty-fifth Division was assigned to Comrade Zhu De's command, who was then the commander of the Ninth Army.

After the victory of the uprising, the planning of military actions, the organization of power, the formulation of land policies, the determination of financial and labor policies, the development of propaganda work, the suppression of counter-revolutionaries, the strengthening of party organizations, etc., were all urgent tasks that needed to be carried out. The following is a detailed account of the progress of these tasks.

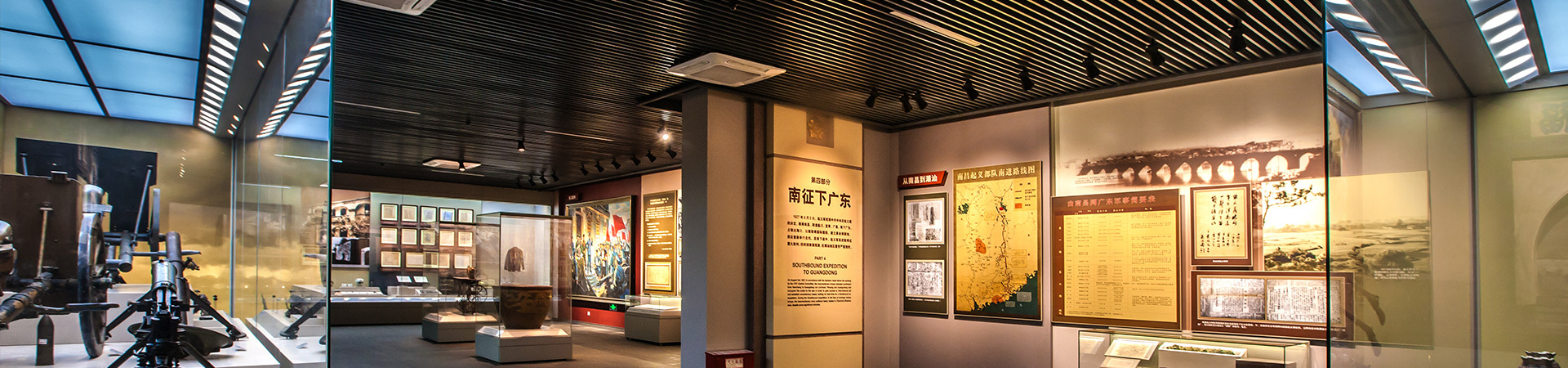

1. Military plans and the process of returning to Guangdong

(1) Discussion on the route back to Guangdong

Regarding the issue of the route back to Guangdong, there were two opinions at the time: one opinion advocated taking the route from Zhangshu, Ganzhou, via Shaoguan, directly to Guangzhou; the other opinion advocated taking the route from eastern Ganzhou through Xunwu directly to the Dongjiang River, believing that this route could avoid enemy attacks and quickly connect with the peasant uprising in Dongjiang. At that time, most comrades supported the second opinion, with only a few military comrades and some non-military comrades advocating the first opinion, resulting in the decision to take the route through eastern Ganzhou to Dongjiang.

(2) From Nanchang to Ruijin

From August 3 to 5, the army left Nanchang one after another and advanced towards Linchuan. The weather was extremely hot, and the roads were mostly mountainous, with a daily march of sixty miles, but in reality, it was often over a hundred miles. The soldiers had a heavy burden, each carrying two hundred and fifty to three hundred rounds of ammunition, and machine guns and artillery were all carried by themselves (due to the lack of laborers). There was no support from farmers along the way, and due to the influence of the reactionary propaganda (Yang Ruxuan had previously sent telegrams to various counties, saying we were bandits implementing communal marriage), the farmers fled upon hearing the news. Food and drink were completely unavailable, and it was difficult to obtain even a bowl of porridge throughout the day. When thirsty, they drank dirty water from the fields, resulting in many soldiers dying from illness, with corpses lining the roads. At the same time, there were often no military doctors or health organizations in the army, making it impossible to treat the sick. Additionally, the propaganda work was extremely poor, and the soldiers did not understand the significance of this uprising, leading to a significant decline in morale and many fleeing. Within just a few days of marching, the strength had already decreased by more than one-third, nearly half of the ammunition was abandoned, mortars were almost completely lost, and several artillery pieces were also left behind, with nearly four thousand soldiers fleeing or dying from illness.

The Tenth Division, led by Cai Tingkai, upon reaching Jinxian, resolved our main force in that division, the Fan Jin Regiment (the Thirtieth Regiment), and moved to Fujian. Originally, the advisory group had decided that the Tenth Division would take the extreme left route, nearly a hundred miles away from the central route, making it impossible to monitor.

Each unit arrived in Linchuan after three to five days of marching. They stayed in Linchuan for three days, and the propaganda work towards the outside and the army only began then (the front committee had just decided on many propaganda plans), and there was also considerable organization within the party in the army and the army itself, so the situation was relatively better after departing from Linchuan, with a slower march (averaging about fifty miles per day), allowing the soldiers to rest a bit, and the weather was also cooler. However, the farmers along the way, influenced by the AB group’s propaganda, were very fearful of us, and for several days, not a single person was seen. For example, in Yihuang County, which originally had nearly twenty thousand people, when we arrived, only forty-eight elderly men and women remained (they had been harassed by bandits before we arrived). It was only after passing Shicheng that the situation improved somewhat.

Upon reaching Linchuan, because the staff of the Twentieth Army and Eleventh Army had fled, there was a complete risk of leaking the original military plan, so it was decided to go from Guangchang to Ruijin and then change the route to Tinghang (the abbreviation for Tingzhou and Shanghang) to reach Dongjiang.

Our army set out from Guangchang, advancing in two columns. The 11th Army was the right column, and the 20th Army was the left column, agreeing to meet in Rujin on August 18th in Rentian City. The 50th and 60th regiments of Qian Dajun's troops were deployed in front of Rentian City, intending to block our army's entry into Guangdong. On the morning of the 18th, Comrade He Long led the entire 1st and 2nd Divisions and the 1st and 2nd regiments of the 3rd Division to attack; at the same time, he ordered the 3rd regiment of the teaching group and the entire 6th regiment to provide cover. In the afternoon of the 18th, we made contact with the enemy. Although the enemy had only two regiments, they were well-trained and thus could resist fiercely until the next morning when they began to retreat. The 11th Army arrived too late, and the 20th Army was almost broken by the enemy. Our 3rd regiment commander was killed, and the 4th regiment commander was injured (he died in Shanghang), with over ten other company and platoon leaders wounded, and more than a hundred soldiers injured. On the 19th, the Revolutionary Committee and the rear guard all arrived in Rujin City. At that time, the enemy was retreating towards Huichang, and the teaching group’s 1st and 2nd regiments pursued, stopping at Xiefang, fifty miles from Rujin.

In Rujin, we obtained many documents from the enemy, which revealed their plans to attack our army, and learned that the enemy had Qian Dajun and Huang Shaohong's troops in Huichang, totaling about eighteen regiments. Thus, we changed our plan, deciding to first break the enemy in Huichang, then return to Rujin, and then take the route through Tinghang to Chaozhou and Shantou (the combined name of Chaozhou and Shantou. — Editor), fearing that if the enemy in Huichang was not defeated, they could attack our rear at any time; at the same time, the route through Huichang to Xunwu to Dongjiang Mountain was very long, making supply extremely difficult (according to later investigations, this was not the case), so we had to first attack Huichang and then return to Min'nan to take Dongjiang.

As the enemy's Qian Dajun troops retreated from Huichang, they concentrated their rear forces in Huichang City. At that time, there were two opinions on our side: one, led by Zhou Enlai, He Long, Liu Bocheng, Ye Ting, and others, advocated attacking the enemy in Huichang and aimed to annihilate them. The second, advocated by the Russian advisor Ji Gong, suggested avoiding battle and quickly moving to Tingzhou and Shanghang to enter Guangdong. As a result of the debate, the majority decided that Ye's troops would advance towards Luokou that day. The 24th and 25th Divisions were the main forces attacking the enemy in Huichang; the 6th regiment of the teaching group and the 5th regiment of the 2nd Division were designated as feint attack troops. It was decided to launch a general attack on the enemy at dawn on August 24th. The enemy's main force was about six thousand men, roughly equal to our attacking troops. At six in the morning, our feint attack troops first made contact with the enemy, and around seven, Ye's troops engaged the enemy. However, the enemy resisted fiercely until four in the afternoon when Ye's troops finally entered Huichang City, capturing over a thousand enemy weapons and more than nine hundred prisoners, and seizing a large amount of enemy abandoned supplies, while our army suffered over eight hundred casualties. The enemy retreated towards Xunwu, and our army only pursued for thirty miles before returning. On the 26th, the enemy, unaware of their defeat in Huichang, advanced from Luokou with over two thousand men, but were defeated by the 11th Army. On the 27th, our army completely returned to Rujin and soon advanced from Rujin to Tingzhou.

(3) From Tingzhou to Shantou

While in Tingzhou, there was a detailed discussion about the plan to take Dongjiang. At that time, there were two opinions: one advocated using the main force to go from Sanheba through Songkou to Meixian, then through Xingning and Wuhua to Huizhou, while a small part of the troops (at most two regiments) would head to Chaozhou and Shantou, as it was believed that the enemy was extremely panicked and Chaozhou and Shantou were empty, which could be taken without battle, and that going through Chaozhou and Shantou to take Xingning and Wuhua to attack Huizhou was too slow, with the possibility of the enemy concentrating their forces to attack our army. The second opinion advocated taking Chaozhou and Shantou with the main force, leaving a portion of the troops at Sanheba to monitor the enemy in Meixian, then going through Jieyang to Xingning and Wuhua to take Huizhou, fearing that if the enemy held firm, it would be difficult to obtain outside support. Enlai and Xiyi (referring to Comrade Ye Ting — Editor) both supported the former opinion, while the Russian advisor and He Long, Bocheng, and others supported the latter. At the same time, many officers, after a long march, wanted to rest, so they mostly supported the latter opinion, which was then decided. From Tinghang to Chaozhou and Shantou, there were no battles along the way, and by the time we reached Shantou, the enemy had retreated for two days.

(4) The Battle of Tangkeng and the Loss of Chaozhou and Shantou

It was originally planned to set out towards Jieyang the day after arriving in Chaozhou, but due to the need to gather departure funds, we stayed in Chaozhou for three days before setting out. At that time, the 25th Division remained at Sanheba, and the 20th Army's 3rd Division was stationed in Chaozhou, so only the 24th Division and the 1st and 2nd Divisions of the 20th Army, totaling less than six thousand combat troops, were set to advance.

On September 27th, the command post in Jieyang received a report from Tangkeng, stating that the enemy's Wang Jun and Huang Shaohong troops had a strength of about a thousand men, concentrated in Tangkeng, preparing to advance towards Jieyang to attack our army. That evening, the command decided to use all forces to swiftly eliminate the enemy, so the next morning, the 11th Army's 24th Division and the 1st Division of the 20th Army stationed in Jieyang were all ordered to head towards Tangkeng, and the 2nd Division was also urged to hurry from Chaozhou. However, when we reached about thirty miles from Tangkeng, we discovered the enemy's advance troops and made contact. The enemy was gradually pushed back by our army, and we captured a few prisoners and weapons. That evening, both sides were on high alert about twenty miles from Tangkeng. The next morning at dawn, fighting began again, and our side made considerable progress. By ten in the morning, the enemy still held the high ground, using intense firepower to block our advance. Our army fought bravely against them, with most of our forces reaching the mountainside, and at that time, the 2nd Division of the 20th Army's 4th and 5th regiments arrived, adding fresh strength, and the enemy retreated slightly, allowing our army to completely occupy the high ground in front. However, after our army occupied that high ground, the enemy advanced to another high ground to counter us. From noon until nine in the evening, although our army used extremely intense firepower to bombard the enemy, they still stubbornly refused to retreat, with both sides charging at each other dozens of times, each holding their positions firmly without moving. At this point, our army realized that the enemy had a larger force and their weapons were also very advanced (in fact, the enemy's strength was about fifteen thousand men, three times ours), making it difficult to defeat them, so we decided to conduct a night attack, ordering the 71st and 72nd regiments of the 24th Division to charge with bayonets, attempting to break into the enemy's formation while the 1st and 2nd Divisions provided cover with intense firepower. The attacking troops used flames as a signal, aiming to encircle and capture enemy weapons. However, after charging for two hours, not only did we not see flames, but we also saw our soldiers retreating in confusion. Upon questioning, it was said that the enemy had prepared, and when our army charged, they remained very calm, surrounding and capturing our soldiers. As a result, those unwilling to surrender charged in and then retreated, going back and forth, suffering extremely heavy losses. At this point, the only remaining force that could regroup and advance was the 4th regiment of the 2nd Division, which was already limited in number. At this stage, the commander saw that our side had suffered excessive losses and that the entire army was running low on ammunition, making it impossible to continue supporting, so he ordered a retreat. After the retreat order was given, each division counted their numbers and found that they had lost half. Thus, the 1st Division took on the task of covering the retreat, and the entire army retreated towards Jieyang.

At the same time as the Battle of Tangkeng, the enemy attacked Chaozhou with part of their forces and used their navy to attack Shantou. Although the enemy attacking Shantou was repelled, Chaozhou was lost, and thus Shantou also had to be abandoned.

On September 29, after our army retreated from Tangkeng, we realized that we could not hold Jieyang, so we decided to occupy Chaozhou. When the troops were nearing Chaozhou, we changed our plan and advanced towards the Hailufeng area, intending to quickly capture Huizhou. Therefore, by October 1, our army's main force had moved to a place about forty miles from Jieyang at the artillery crossing. By the time we finished crossing the river, it was already late in the day, so we camped about fifteen miles from the artillery. The next day (the 2nd), we marched sixty miles and camped at Guiyu, with nothing happening all day. On the 3rd, we set out again from Guiyu. The First Division was the vanguard, the Second Division followed, and the command headquarters was next, with the 24th Division of the 11th Army as the rear guard. On this day, we received reports that there were enemies attempting to encircle our army from the Puning area, so we ordered a departure at 3 AM. However, the First Division had not completed its departure by 6 AM, resulting in a very crowded marching route in the first half of the day, taking half a day to cover just over twenty miles. By 3 PM, when our 20th Army had passed near Liusha's Wushi, the command headquarters and the 24th Division were still at Wushi. Suddenly, we discovered the enemy in the mountainous area ahead, firing at our army. At that time, the command headquarters realized that the 20th Army had already passed, and only the 24th Division and the command headquarters were cut off by the enemy, which was very unfavorable. Therefore, we ordered the 24th Division's 70th, 71st, and 72nd regiments to occupy positions on the left, right, and front to cover the command headquarters' passage. Unexpectedly, as soon as we allocated our forces, the enemy's gunfire erupted. Along the way, scattered troops and various baggage saw the situation and fled, resulting in a chaotic scene with mixed personnel, making it difficult to maintain command and execute orders. Although the command headquarters tried hard to stop the retreat, it ultimately could not enforce compliance with orders, so we had to gather all the soldiers to hold the key routes, allowing the remaining personnel to escape. Only the riflemen were ordered to join the soldiers to plan for a final resistance. After the battle, only a few hundred men remained in the 24th Division, retreating to Hailufeng. The remaining troops of the 20th Army were disarmed by the enemy just before reaching Lufeng.

At the same time as the battles at Tangkeng and Wushi, the enemy sent three divisions to attack the 25th Division, which was stationed at Sanheba. Under the leadership of Comrade Zhu De, the 25th Division fought fiercely with the enemy for three days and nights, causing the enemy to retreat. However, the 25th Division also suffered heavy casualties, leaving only about two thousand men and over a thousand rifles. Comrade Zhu De then led this remaining part of the troops to withdraw from Guangdong, passing through Jiangxi and entering southern Hunan to conduct guerrilla warfare. Later, in April 1928, they reached the Jinggangshan area and joined forces with the troops led by Comrade Mao Zedong.

2. Organization of Power

Before the uprising, the party decided that, in principle, a democratic revolutionary power led by the proletariat and supported by the petty bourgeoisie of workers and farmers should be established. In practice, this meant organizing a power structure dominated by Communist Party members in alliance with the left wing of the Kuomintang, nominally using the name of the Chinese Kuomintang Revolutionary Committee to oppose the Nanjing-Hankou government. After the uprising, a revolutionary committee was formed in the name of a joint meeting of the provincial party departments of the Kuomintang and special municipal party departments, as well as overseas party representatives.

There was debate regarding the selection of members for the revolutionary committee. The main point of contention was the issue of Zhang Fakui. At the beginning of the uprising, there were differing opinions on how to approach Zhang Fakui, with some arguing that the decision to rise should not depend on Zhang's attitude, while others insisted that Zhang must be won over for the uprising to succeed. Although the final decision was to proceed regardless of Zhang's stance, in many respects, it still reflected a policy of compromise towards Zhang. For instance, on the second day of the uprising, He Ye sent a telegram to Zhang, welcoming him to Nanchang, and also used the name of a mass organization to extend a welcome to Zhang (these actions were not formally decided by the previous committee, and at the time, some comrades formally opposed them). When discussing the selection of members for the revolutionary committee, Xu Te-li and Tan Pingshan strongly advocated for Zhang's inclusion; Zhou Enlai and Li Lisan supported excluding Zhang but did not push hard; and Yun Daiying and Peng Pai had no strong opinions. As a result, Zhang became one of the members of the presidium, and Huang Qixiang and Zhu Huiren were also listed among the revolutionary committee.

After arriving in Ruijin, we received newspapers from Shanghai, which revealed that not only had Zhang Fakui and others raised a clear anti-communist banner, but also that the so-called leftist elements in various provinces had completely surrendered to the Wuhan government, which had effectively capitulated to Chiang Kai-shek. Meanwhile, warlords in various provinces were using the name of the Kuomintang to close down labor unions and peasant associations, massacring the working and farming masses. Therefore, the previous committee meeting decided that the name of the Kuomintang had been rejected by the working and farming masses, and that the nature of the power must be fundamentally changed to establish a proletarian-led government of workers and farmers. However, under the workers' and farmers' government, there should be a policy of uniting with the impoverished petty bourgeoisie, which in practice meant a government where the majority were workers and farmers, and Communist Party members held a majority. It was also decided that rural power should be completely in the hands of the peasants, with a focus on the poor; in urban areas, workers must hold an absolute majority; and in county power, workers and farmers should also hold an absolute majority. After arriving in Tingzhou, it was further decided that the government would still use the name "National Government" to deal with foreign affairs and avoid excessive interference from imperialism, and it was decided to appoint Tan Pingshan as chairman, including Chen Youren and others as permanent members of the National Government. Although many workers and farmers were included among the government members, in reality, this was almost a perfunctory measure regarding the original policy, as except for Comrade Su Zhaozheng, they were merely nominal government members.

3. The Program of the Land Revolution

When in Jiujiang, there were differing opinions on the program of the land revolution. Comrades Li Lisan and Yun Daiying advocated for a program to confiscate the land of large landlords, arguing that the main significance of the Nanchang uprising was to continue the struggle for land confiscation and implement the land revolution. Tan Pingshan opposed proposing a program to confiscate large landlords' land, claiming that doing so would provoke a stronger alliance of reactionary forces and divisions within the army. The debate was intense and could not be resolved, so we had to report to the central committee to seek approval. Later, when Comrade Zhou Enlai arrived in Xun, he conveyed the central committee's opinion that the land revolution should be the main slogan, leading to the final decision.

The second discussion regarding the land program took place after the Nanchang uprising. At that time, the Farmers' and Workers' Committee proposed a regulation for the liberation of peasants that included "confiscation of land from landlords with more than 200 acres." During the discussion, there were many differing opinions: some believed that the 200-acre limit was still too low and advocated for confiscating land from landlords with 300 to 500 acres or more; others suggested postponing the land program decided in Wuhan and confiscating land from landlords with "50 acres of fertile land and 100 acres of barren land"; and there were even those who suggested not proposing anything at all. Finally, Comrade Daiying stated: "Our August 1 revolution is to realize the land revolution, so we have decided on the land program, and we must start implementing it along the way. As long as we can truly implement it, confiscating land from landlords with more than 200 acres is also good." Therefore, the original proposal of the Farmers' and Workers' Committee was passed.

After this program was decided, many comrades were skeptical, and discussions were held among the Guangdong farmers in the army along the way. One farmer responded candidly, saying: "If we confiscate land from landlords with more than 200 acres, then the tillers will have no land to cultivate." Because in Guangdong, there are very few landlords with more than 200 acres, aside from many public lands. This statement awakened many comrades' minds, leading to the decision in the subsequent committee meeting in Ruijin to change "confiscation of land from landlords with more than 200 acres" to "confiscation of land," without any acreage restrictions, and to abolish the original farmers' liberation regulations and propose a new amendment.

The third discussion was held in Shanghang regarding the program of the National Government. At that time, the majority of comrades advocated for total confiscation, believing that since the peasants had risen, not only would the land of landlords with more than 200 acres be confiscated, but even the land of self-cultivating farmers with less than 20 acres would also be confiscated. In fact, the average land rights in many places in Hunan were examples of this. Our government certainly cannot suppress them just because they exceeded the land policy limits and infringed upon the interests of the petty bourgeoisie. Therefore, we should fundamentally propose the slogans of "confiscation of land" and "those who cultivate the land should own it." As for the methods to win over small landlords, other policies could be used, such as issuing interest-bearing bonds that do not require repayment after the confiscation of small landlords' land. Zhang Tieli's opinion was that small landlords should still be given considerable protection, thus advocating for the confiscation of land from large landlords with more than 50 acres. Since the majority opinion was to advocate for total confiscation, the decision at that time was still "confiscation of land, those who cultivate the land should own it." The next day, the Guangdong Provincial Committee sent a detailed program, stating that for the land issue, the land of landlords with 30 to 50 acres would be confiscated, while those who relied on rent for their livelihood would not be confiscated, and this had already been publicized in various places. Therefore, Zhang Tieli convened another meeting, and the opinion of "confiscation of land from large landlords with more than 50 acres" was passed.

4. Labor Protection Policy

Before and after the uprising, little attention was paid to the workers' issues. It was not until after Ruijin that the preliminary committee discussed a program regarding labor protection. As a result, the Agricultural and Industrial Workers Committee proposed a temporary labor protection regulation, consisting of nineteen articles, which included an eight-hour workday for industrial workers, a ten-hour workday for handicraft workers, compensation for work-related injuries and deaths, pensions for deaths due to illness, unemployment insurance, and protection for child and female workers, as well as eight weeks of rest before and after childbirth. The articles were very brief and were passed without serious discussion.

5. Financial Policy

After the Nanchang Uprising, the Revolutionary Committee was established and discussed the issue of financial policy. At that time, opinions were almost unanimous in principle, which was to fundamentally change the previous warlord's financial policy, shifting the financial burden from the poor workers and farmers to the wealthy class, and decided to immediately abolish the tax and other harsh levies (there were opposing opinions at that time). After arriving in Linchuan, military salaries became increasingly difficult (due to the inability to use paper currency), and there was an urgent need to find ways to raise cash, which led to a major discussion about financial policy. In summary, there were two opinions: one advocated for continuing the old policy, which meant withdrawing funds, distributing funds, and borrowing funds whenever arriving in a city, effectively utilizing the general local gentry to raise funds. The result of this policy would naturally shift the burden onto the poor workers, farmers, and small merchants, while large merchants and gentry could profit from it; the other advocated completely abandoning the old methods, stating that the current policy should be to requisition (such as requisitioning grain from landlords), confiscate (confiscating the property of reactionary gentry), and impose fines on the gentry. Tan Pingshan and others supported the former opinion, while Zhou Enlai, Li Lisan, and Yun Daiying supported the latter. Which of these two opinions was correct is obviously clear; if we adopt the former financial policy, it would not only be no different from the warlords' methods of raising funds but would also undermine our fundamental policy (such as establishing workers' and farmers' power and suppressing the gentry). Therefore, although there were debates in the meeting, the reasons for the former opinion were insufficient, and it was naturally decided to adopt the new financial policy. However, when it came to implementation, problems arose. In the eastern Jiangxi region, due to the lack of support from farmers, it was difficult to investigate who the large landlords and gentry were, while the old methods could raise a small amount of funds. Thus, the methods of raising funds from Linchuan to Ruijin were extremely chaotic. Tan Pingshan also came up with a "principle": "As long as there is money, the policy does not matter." When they reached Tingzhou, because the business association recognized the fundraising, Tan Pingshan advocated abandoning the policy of punishing the gentry, but ended up being greatly deceived. Originally, the Tingzhou business association acknowledged that they would pay 60,000 yuan within three days. Tan Pingshan then allowed the business association to distribute funds in urban and rural areas, even to self-cultivating farmers with less than ten acres and very small grocery stores, distributing them amounts ranging from ten to eight yuan, while those with assets over 100,000 yuan only contributed three to five hundred yuan. As a result of this search, only over 20,000 yuan was raised in three days, causing a great uproar in the city. Therefore, the Revolutionary Committee discussed again, and everyone strongly criticized the inappropriateness of this policy, thus deciding to completely abandon the old methods and adopt the new policy, conducting a large-scale crackdown on the gentry in Tingzhou, implementing confiscation and fines, and returning many of the funds that had been distributed to the poor workers and farmers. In just two days, over 40,000 yuan was obtained. At the same time, it was decided that after arriving in Guangdong, the new policy would be fully implemented, and a wartime economic committee would be organized to manage everything. However, when they reached Chaoshan, the new policy was completely abandoned. At that time, Tan Pingshan put forward two reasons: first, large-scale requisition and confiscation might provoke imperialist intervention; second, Chaoshan was the location of the National Government, and large-scale requisition and confiscation would result in a complete halt to commerce and chaos, allowing reactionaries to expand their propaganda. Thus, the financial policy remained unchanged, and the wartime economic committee was doomed from then on.

6. Suppression of Reactionaries

Under the Revolutionary Committee, a Political Security Office was established, specifically for the suppression of reactionaries, and it was decided to adopt a policy of severe suppression against reactionaries such as gentry. This policy initially could hardly be implemented in the eastern Jiangxi region due to the lack of support from the peasant movement, and only about thirty gentry and a few members of the AB group were killed in places like Yiqian, Guangchang, Pingxiang City, Ruijin, and Huichang, and four gentry were killed in Tingzhou. At that time, the Political Security Office was preparing for a large-scale suppression of reactionaries after arriving in Guangdong, but the result was that only three were killed in Chaozhou, four in Dapu, and twelve in Shantou, and the originally planned policy could not be realized. The main reasons were: first, important reactionary figures had already fled upon hearing the news, making it impossible to capture them. Second, the peasant movement in the Chaoshan area was extremely weak, and the views of the comrades in charge were very confused. For example, in Dapu, when local comrades were asked to provide a list of reactionaries for arrest, they noted on the list that certain individuals should be sentenced to five months, three months, or life imprisonment, etc. In other places like Sanheba, there was completely no organization of peasant associations, making it impossible to arrest anyone. Third, there was a subjective abandonment of the policy of suppressing reactionaries; for instance, in Tingzhou, Chaozhou, and Shantou, Tan Pingshan repeatedly requested to delay the handling of reactionaries, and Xu Guangying was appointed as the head of the Shantou Public Security Bureau. Before the reactionaries could be punished, they first executed three poor people who were caught looting. One of the maritime workers saw this and immediately said, "This is Chiang Kai-shek's third army." When Chaoshan fell, there were still dozens of reactionaries in prison (most of whom were sent by the unions), and they could not be executed (they could not shoot at night, and there were no knives). When the reactionary army arrived, they naturally came out immediately, becoming even more reactionary.

7. Propaganda Work

Under the Revolutionary Committee, a propaganda committee was established to manage propaganda work, and a General Political Department was also set up to manage internal propaganda within the army. However, the propaganda work this time was poorly executed. The errors in slogans and policies were due to the overall policy errors and could not be blamed solely on the propaganda work. However, the significance of the "August 1" revolution was not only not deeply understood by the masses, but even the soldiers of both armies did not understand it; soldiers of the 11th Army even said after the defeat, "The Fourth Army and the 11th Army were originally one, it was Ye Ting who ruined it." This was all because the propaganda work did not reach the soldiers.

8. The Situation of Workers and Peasants' Movements During the March

In eastern Jiangxi, apart from finding the party's special branch organization in Linchuan and Ningdu, we did not find any local party organizations in the other places we passed through, and our army could not receive any help from the farmers. However, the reactionary A B regiment had a significant influence in eastern Jiangxi, so our army not only could not get help from the farmers in this area but also faced many obstacles.

Political workers along the way promoted the Guangdong peasant movement as very good, claiming that once we reached Guangdong, the farmers in each county would immediately rise up to support us, and there would be no difficulties with laborers, food, etc. At that time, not only did the general soldiers believe such propaganda, but all comrades thought the same. However, upon entering Guangdong, people were greatly disappointed. The situation of the farmers towards the army was even worse than in Fujian. For example, in Dapu, there had already been an organization of workers and peasants to fight against the reactionaries, and they had been preparing for an uprising for two to three months, but they only had a very weak and immature military arrangement, completely neglecting the work of mobilizing the masses and organizing them. As a result, when our army arrived, they did not even dare to arrest the reactionaries. When the army was about to depart, they were asked to gather a hundred farmers to organize a peasant army to defend the county's power, but only over fifty people were gathered.

Sanheba is extremely important militarily, but there is no farmers' association organization in the area. Songkou is the location of the eighth regiment of the workers and peasants' army, with only about seventy farmers' soldiers, and the peasant masses have not risen up. Our army handed over one hundred and fifty guns to them, but they could not find farmers to take them.

Everyone imagined that the workers' movement in Shantou must be very developed because it had gone through a long struggle during the provincial and port strikes. However, upon arriving in Shantou, preparations were made to completely replace the previous police and organize a volunteer team of five hundred workers to take their place. After three days of calling, only over seventy people were gathered, and they were not very willing because their pay and food were unsatisfactory.

Shantou also went through several months of preparation for the uprising, but it only focused on military technical preparations and did not know how to politically mobilize the masses, resulting in the masses not being able to rise up.

The peasant movement in the eastern (western) Chaoshan area is relatively good. The peasant masses have gone through a long struggle, and the military preparations for the uprising are also relatively complete (still lacking in political mobilization and organization of the masses). The masses also spontaneously rose up to participate, so before our army arrived, the peasant army had already occupied the cities of Hailufeng. When our army arrived, the peasant army in Chaoyang and Jieyang had also occupied the county seat, and the farmers from the four townships of Puning rose up to besiege the county seat. The reactionaries held the county seat firmly, with over eight hundred guns, machine guns, and cannons, and the peasants could not break through the siege, sending people to request military assistance. At that time, a battalion from the 11th Army was sent to assist in the attack, and within a few hours, they broke through. They could have gathered and eliminated the counter-revolutionaries in Puning, but the commander of this battalion (comrade) did not allow the peasant army to enter the city (for fear that the peasant army would kill too many), and at the same time announced:

"The revolutionary army is a non-disruptive army and will never kill indiscriminately." When the army retreated, the peasant army also did not dare to kill. The peasant army thought: "The army is our own army, and it is not appropriate to kill the reactionaries in large numbers when breaking the city, or to follow the predetermined policy of the organization."

Only the peasant army in Chaoyang had killed many reactionaries after breaking the city, and the farmers welcomed it exceptionally. The farmers in Fuyang fought fiercely with the landlords for several days, and after the army's assistance disarmed the militia, the farmers killed many landlords. However, the reactionaries in these areas had not been completely eliminated, and militarily they had completely failed. Therefore, the peasant armies in various places had no choice but to retreat to the mountains.

Nine Party Organization

"On the surface, the August 1st revolution seems to be completely under the party's guidance, but in reality, it is merely the personal guidance of many Communist Party members."

The Central Committee's "August 7th" emergency meeting did not have clear decisions regarding the policies after the "August 1st" revolution, such as the Kuomintang issue, power issue, financial and economic policies, and foreign policy. The comrades of the front committee only learned about the "August 7th" emergency meeting after arriving in Shantou. After two months of marching, they had become almost like wild people, not only unaware of the party's situation but also completely ignorant of the national political situation. They only learned about Chiang Kai-shek's resignation after seeing the "Shen Bao" in Tingzhou.

The members of the front committee, originally according to the Central Committee's orders, did not include Tan Pingshan, but at that time Tan Pingshan bore a significant political responsibility, and the Central Committee did not replace him. Therefore, the result of the front committee's discussion was that Tan Pingshan had to participate in the front committee meeting. Before the Nanchang uprising, the front committee was relatively well organized, but later the revolutionary committee was established, and the members of the front committee all joined the revolutionary committee and took on heavy responsibilities, while various technical tasks were also canceled. Thus, the front committee became the party group of the revolutionary committee. The few people responsible were all scattered in different directions, making it difficult to gather for meetings. Therefore, apart from a few major fundamental policies, many important issues were handled at the discretion of the responsible comrades, and even violations of established policies could not be corrected or punished. For example, in Shantou, there were matters such as contacting Zhang Fakui again and appointing Chen Jiongming's troops as brigade commanders, which several comrades participating in the front committee were completely unaware of until they heard about it in Hong Kong.

There were about two hundred sixty people working in the revolutionary committee, including over one hundred eighty comrades, but they only organized after arriving in Tingzhou, holding two general meetings and several branch meetings. As for their work, the front committee was unable to manage and guide it at all.

The party organization in the military department is relatively good, and there are also relatively many meetings, but the relationship with the front committee is not close because the military department is independent in organization, and all political guidance for the army must go through the military department completely. However, the party committee in the military department is also politically weak, so the party's political guidelines are difficult to penetrate into the comrades in the army.

The party organizations in the various places we passed through were exceptionally immature. Not to mention in eastern Jiangxi, even in all the party organizations in eastern Guangdong, they were not organizations of the masses' struggles. Some places had made great efforts to prepare for uprisings, but only focused on military technology and did not delve into the masses. (The above is edited based on the materials published in the 7th and 13th issues of the "Central Communications" in 1927, and also refers to some other literature.)

"Copied from the Party History Data Room of the Central Committee's Propaganda Department: 'Party History Data' Issue Six"

recommend products

Copyright 2021 Nanchang August 1st Uprising Memorial Hall All Rights Reserved |Bayi Pavilion WeiboWebsite construction:www.300.cn